History

An overview of the history of St. Mary's Church, Stebbing

Background History

Settling roughly along the east bank of Stebbing Brook; a tributary of the River Chelmer, (1) the village of Stebbing and its hamlets envelope a huge swathe of historical events, some of which have consequences still reverberating today. Being located just north of Stane Street, the major Roman road running from St. Albans to England’s oldest town Colchester (1) , has been a major influence in Stebbing’s on-going role and development. Pre-historic existence here is hard to find, but various excavations have proven Roman settlements in and around Stebbing – including traces of a Roman building beneath the Green (2) , slivers of Roman cement discovered externally on the church vestry, along with three fragments of Roman tegula (a flat roof tile) and rubble and debris in the foundations (3) .

The post-Roman era saw the arrival of the Saxons, then the Danes and Stebbing found itself in the historic Hundred of Hinckford. In the time of Edward the confessor (1042-1066) (1) The lands of this parish were in the possession of a Saxon thane named Siward. Following William the Conqueror’s successful arrival from Normandy in 1066, the general survey which formed the Domesday Book, show the lands of this parish belonging primarily to two Norman lords, Henry de Ferrers, and Ralph Peverel – with the de Ferrers family ultimately holding the longest lasting influence. (4 & 8) Initiated by William the Conqueror in 1080 and completed in 1086, The Domesday Book states regarding Stebbing: ‘a priest has always been on this place’ and lists under ‘Land of Henry of Ferrers’, that the households included ‘8 villagers. 33 smallholders … 1 priest’ (4) & (8). Today, the Domesday blue plaque issued in 1986 to celebrate 900 years of Norman heritage, can be seen on the entrance to the church tower (5).

The church’s early years

Section Footnotes

(1) https://www.hundredparishes.org.uk/FreshFiles/PDFs/STEBBING.pdf (2) Norman Scarfe, Essex A Shell Guide, p.165 (3) Stebbing Church’s archeological report into the vestry work 1993 – DD Andrews (Essex County Council Field Archaeology Group) – (unbound document) (4) Thomas Wright, The County of Essex, vol 2, p.50 (5) https://opendomesday.org/place/TL6624/stebbing/ (6) Thomas Wright, The County of Essex, vol 2, p.52 (7) Durrants Handbook for Essex/Millar Christy, p.199 (8) RS & RL Greenlee, Stebbing Genealogy, page 15-21 (9) 6 page typed document c 1990’s (10) A cartulary or chartulary is a medieval manuscript volume or roll, containing transcriptions of original documents relating to the foundation, privileges, and legal rights of ecclesiastical establishments (11) Michael Gervers, The Cartulary of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in England, part 2; Prima Camera Essex (12) Michael Hodges, The Knights Hospitaller in Great Britain in 1540 (13) Great tithes were corn, hay, wood (p.14 Hodges/p.111 Fry). A tithe is 10% of production. Small tithes included livestock, butter, cheese, fruit, vegetables, honey, wax, flax, wool, hemp, rushes, game, fish (14) SJB Fry, Function, Tradition, Ideology or Patron: What influenced the architecture go Knights Hospitaller Commandery Chapel and associated Churches in Britain 1140-1370

Section Footnotes

(11) Michael Gervers, The Cartulary of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in England, part 2; Prima Camera Essex (12) Michael Hodges, The Knights Hospitaller in Great Britain in 1540 (15) The crusades are sometimes referred to in numerical order, but historically are also known by differing names. Date-wise: the 1st (1096-1102); 2nd (1147- 49); 3rd (1189-92); 4th 1202 -4); 5th (1217-29; 6th (1228-29); 7th (1248-54); 8th (1269-72); 9th (1271-72) crusades, were then followed by continued battles – for full date chronology 1095-1892, see Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History

Local churches

Section Footnotes

(12) Michael Hodges, The Knights Hospitaller in Great Britain in 1540

Appropriated Churches

Chaureth, with its administrative role, was the first Hospitaller commandery established in Essex (11, p.lvii/ch 3). It came into being following the conveyance of Chaureth church and land of Richard Pigot (or Picoti) to the Order, by Alfred de Bendaville and his wife Sibyl in 1151, with the grant confirmed by Gilbert of Clare, first earl of Hertford in 1152. Further grants were added, and grant of the church re-confirmed by succeeding generations of Clare’s still being recorded at 1268. (p.lvii/lviii ch.3 Gervers) Around 1255, Chaureth became subordinate to the new Essex commandery at Little Maplestead, meaning that all lands administered by Chaureth, which at its height included eighty parishes in Essex, were then all under the jurisdiction of Little Maplestead. Additional administrative changes led to the appropriation of Chaureth church to Clerkenwell at some point prior to 1338 (p.lviii ch. 3 Gervers). In fact, it would appear that Chaureth’s more isolated location away from key road or water transportation, was the reason it eventually lost central administrative control, in favour of Little Maplestead (p.xcvi ch.5 Gervers). A transcription relating to the manuscript entries connected with and Chaureth church (pages 124 to 176) can be read in ‘The Cartulary of The Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in England, part 2; Prima Camera Essex’, edited by Michael Gervers

Section Footnotes

(11) Michael Gervers, The Cartulary of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in England, part 2; Prima Camera Essex

The Prima Camera Essex notes (11): ‘the great majority of the entries under Stebbing titulus pertain to land which supported the church, namely War field’, which is located where the church’s car park is now located. ‘In the late twelfth century this field belonged to the monks of St. Mary of Hambeye in Normandy, whose second abbot Rocelin, held it of the alms of Thomas Coulonces. In 1180, Rocelin and the monks leased the land to Warin, son of Guy the miller …in 1256 the (Hospitallers) conveyed the entire field to (the vicar) …Ricardi Gifferd … for rent of 32s. The Order was to render half this amount to the abbot of Hambeye and would retain the other half for itself (p.lx11/ch.3 Gervers) … War field contained 50 acres.’ (16) Noting various ‘claims and quitclaims’ etc, Prima Camera Essex concludes from a ‘document attributed to c1255, Ralph North conveys homage and service arising from land in Alnoldshey field in Stebbing to the Hospitallers at Chaureth… The church of Stebbing and the lands associated with it, seem to have been administered … for the entire period from its donation in 1181/2 to the time, probably in the third quarter of the thirteenth century, when Cheruth was replaced by Little Maplestead as the sole Essex (commandery) and when the two appropriated churches were undoubtedly absorbed by Clerkenwell.’ (p. lxiii/ch.3 Gervers) A transcription relating to the manuscript entries connected with Stebbing church (pages 185 to 216) can be read in ‘The Cartulary of The Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in England, part 2; Prima Camera Essex’, edited by Michael Gervers

Section Footnotes

(11) Michael Gervers, The Cartulary of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in England, part 2; Prima Camera Essex (15) According to the tithe map of 1839, there were 17 acres 56 silicons in Upper War field, 15.75 acres 26 silicons in Middle War field, 10.75 acres 8 silicons in Ten Acre War field, and 5.25 acres 35 silicons in Green War field (ERO D/CT 332 and D/CT 332A) – p.lx111 footnote/The Cartulary of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in England, part 2; Prima Camera Essex, Gervers

The Stone Screen

References/Bibliography

https://www.hundredparishes.org.uk/FreshFiles/PDFs/STEBBING.pdf Essex, A Shell Guide, Norman Scarfe, reprinted 1975 Stebbing Church’s archaeological report into the vestry work 1993 – DD Andrews (Essex County Council Field Archaeology Group) – (unbound document) 6 page typed report c 1990’s Thomas Wright, The County of Essex, vol 1, 1831 Thomas Wright, The County of Essex, vol 2, 1836 Stebbins Geneology, RS & RL Greenlee, vol 1 1904 / Domesday book National Domesday Committee https://opendomesday.org/place/TL6624/stebbing/ Durrants Handbook for Essex/Millar Christy 1887 Philip Morant, History & Antiquities of the County of Essex Michael Hodges, The Knights Hospitaller in Great Britain in 1540, 2018 Michael Gervers, The Cartulary of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in England, part 2; Prima Camera Essex edited1996 Joanthan Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History 2014 Third Edition SJB Fry, Function, Tradition, Ideology or Patron: What influenced the architecture go Knights Hospitaller Commandery Chapel and associated Churches in Britain 1140-1370, 2013

The rood screen

One of the chief architectural glories of St Mary’s is the stone rood screen that fills the Chancel arch. It consists of three smaller arches and richly carved canopy work. Only three examples of this style of screen exist, and Stebbing is the earliest example. The other examples are in Great Bardfield, and Trondheim Cathedral in Norway.

In the 15th Century, the screen suffered considerable mutilation to admit a wooden screen, which was erected on the East (Chancel) side of the stone screen. Access to the top of the wooden screen was granted by a door in the north wall of the Chancel, which can still be seen, along with the remains of the stairs up within the vestry. The stairs in the South wall of the nave most likely connected with this rood screen, passing over a canopy covering a chapel in the south aisle. It may be noted that the pulpit is made from old oak, suspected to be taken from the 15th Century wooden screen when it was removed in the 17th/18th Century.

The Stone rood screen was heavily restored and rebuilt in 1884. It was noted by the Rev. C.E. Livesey in 1924 that they soon hoped to complete the rood by instating the two missing statuettes missing from the plinths either side of the central cross. Almost a hundred years on and these figures are still missing! Evidence of the rebuilding of the rood screen in 1884 is all throughout the church; chunks of fine faced stone removed during the repairs sit on may window sills and the credence table in the North East corner of the Chancel consists of two original stones with grotesque figures that came from the springing of the arch in the rood screen.

The doorway, now blocked, that granted access to the 15th Century wooden screen.

The credence table, made from ORIGINAL stone of the rood screen.

The Font

The Font is Octagonal, with a panelled stem, dating from the 15th Century. The cover is of fine oak, and has a plaque dedicated to The Rev. A. R. Bingham Wright, 31 Years vicar of this parish, died June 12 1906 and Mary Sophia Cecily Bingham, his Daughter, Who died Nov 26 1905.

The Font currently stands at the East end of the North Aisle. It was moved to it’s current location in 2000, having previously stood at the West end of the South Aisle, by the South door. It is recorded that prior to the internal re-ordering in 1884, the font stood in the middle of the Chancel.

The Porch

The main entrance to the church is through the South door of the nave. The porch stands at this entrance. Standing in the porch, you can see the original dripstone, which shows that the porch roof was raised up from a gable roof to it’s current flat configuration. The brickwork that raises this roofline dates to the 16th Century.

The porch was refurbished in 1923, where the East window was repaired. The current west window had a brick cross inserted at some point, most likely to stop people climbing through the opening. Inside the porch there is the broken remains of a stoup for holy water.

There are well worn holes over the door, probably a socket for a perpendicular bar to secure the door. It would seem from the groove on the arch that the doors opened inward to the porch at one time.

The interesting double piscina and one of the sedilia arches in the chancel

The Stained glass in Stebbing church

The Stained glass in Stebbing church

Very little, of the original 14th/15th Century-stained glass remains, much of it having been destroyed at the hands of the Puritans.

Fragments which have been recovered, have been fashioned together into the window to the side of the font. A few windows contain other fragmentary remnants of their former past.

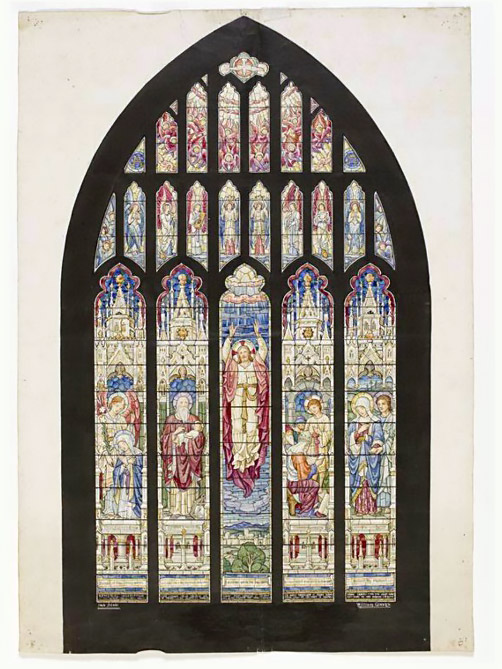

Stebbing church has one stained glass window. This was commissioned to mark the approximate 600th anniversary of the present building. The window was designed by A.K Nicholson and installed in 1924 and it seems that this was paid for by the Stacpoole family; (The novelist and writer Henry de Vere Stacpoole who was a former resident of Rose Cottage at the foot of the church drive).

A design for the beautiful East window in the chancel was commissioned by the renowned stained glass artist William Glasby, this design is now in The V&A museum in London.

It can be seen that his design is echoed in the window designed by A.K. Nicholson

Hatchments

In Stebbing church, behind the altar there are 2 hatchments.

Hatchments were particularly popular in the 18th and 19th century. They are lozenge shaped boards bearing the heraldic details of a particular person. They were a type of funeral flag or banner, historically used to display the coat of arms of a deceased person.

When a notable person died, their hatchment was hung outside their home between their death and their funeral, (sometimes for the whole period of mourning) and they were often carried as part of their funeral cortege. Hatchments were traditionally diamond shaped and were made of wood or canvas, with the coat of arms painted or sometimes embroidered onto them.

The hatchments in Stebbing church are for Arthur Batt and his wife Frances. Arthur died on the 3rd of February 1730 aged 47.

Summers (‘Hatchments in Britain’ vol 6) describes this hatchment as ‘dexter background black, sable a fess ermine between three dexter hands coupled argent’. The crest is a demi lion rampant. The motto reads Mors Janua vitae (death is the gateway to life).

The second hatchment is for Arthur’s wife Frances, who died on 23rd of February 1744.

To the side of the altar, below these hatchments, there is a memorial stone for Arthur and Frances Batt. This too bears their family crest. Frances left a sum of money from which each year money should be given to the poor of the parish.

This charity is still in existence today.

Graffiti in St Mary's Church

Below are examples of just some of the graffiti to be found in Stebbing church. Some of which dates back to about the 15th Century!

Medieval graffiti is often seen as a lost voice, it represents many different things including prayers for the sick and the dead. There are heraldic badges, including a De Bourchier knot and The DeVere mullet. There are games of 3 men’s Morris, compass drawn designs, which were thought to be associated with ritual protection, a family leaving a prayer request, to ward off evil or ill fortune, and there are prayers to Mary.

Here are some examples of what you can see.

From an original painting by Bernard Sickert 1910 ‘Painting of a Wedding at Stebbing’.